Kiel Institute Highlights

The Blue Carbon Wealth of Nations - Nature Capital Valuation

Coastal ecosystems, such as seagrass meadows, salt marshes, and mangrove forests, are valuable to humans in many ways. In particular, they store carbon—and do so with a much higher surface density than forests, for example. They thus make an important contribution to mitigating climate change. Australia’s coastal ecosystems alone, which absorb a particularly large amount of CO2 from the atmosphere, save the rest of the world climate-related costs of around USD 23 billion a year.

Climate policy instruments such as emissions trading schemes are intended to coordinate mitigation activities by providing a price signal for CO2 emissions. Companies can then compare the price of CO2 with the cost of avoiding CO2 emissions to decide which emissions can be beneficially reduced. The price signal on carbon markets depends on the underlying ambition of the policy target. This can be seen from the current price rally in the European emissions trading system in expectation of a more ambitious reduction target for 2030.

Not included in this market are carbon sinks, i.e., forests, moors, and also seagrass meadows. Their carbon uptake is determined by factors such as the levels of CO2 in the atmosphere, ecological processes and feedbacks, and human intervention. Nonetheless, this reduces climate damages and, therefore, has implications for global wealth.

Social cost of carbon – how to price natural services

Such services provided by nature are an integral part of what is known as the “inclusive wealth framework.” Inclusive wealth is defined as the aggregate of all natural and human-made capital stocks, valued at their shadow price—that is, the estimated financial value that a commodity or service provides for societal welfare, rather than a market price. These shadow prices are affected by factors such as the scarcity of resources and expectations about future management of human-made and natural capital stocks.

Climate change reduces inclusive wealth, so CO2 emissions are like a negative investment in inclusive wealth.

The appropriate shadow price to assess this negative investment is the “social cost of carbon” (SCC). The SCC is an estimate of the economic damages that would result from emitting one additional metric ton of CO2 into the atmosphere at any point in time. It takes into account both the benefits and drawbacks of CO2 emissions. Overall, they must nevertheless be considered as costs, since there are more negative impacts of climate change than positive ones.

The SCC is a global measure, obtained by adding up national damage estimates of the social cost of carbon of individual countries (country-level social cost of carbon, CSCC). Recent studies have integrated climate models and economic models to estimate the CSCC for all countries in the world.

Reduced climate damage thanks to blue carbon wealth

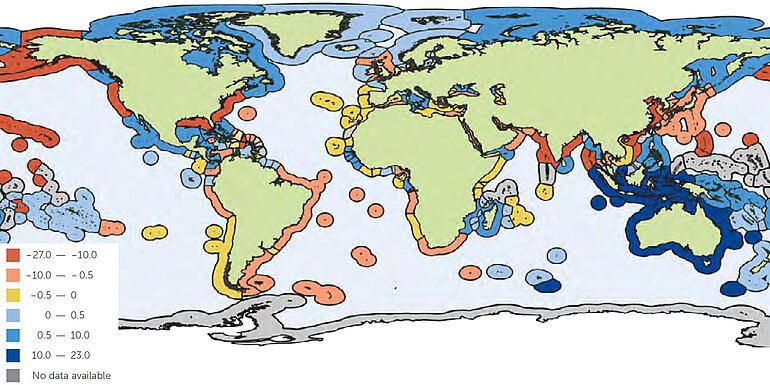

In the same way as CO2 emissions are a negative investment in inclusive wealth, ecosystems that absorb CO2 from the atmosphere enhance inclusive wealth. In our study, we focused specifically on carbon sequestration by coastal ecosystems, such as mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows—known collectively as “blue carbon.” Each metric ton of CO2 absorbed by these coastal ecosystems increases global inclusive wealth by an amount equal to the SCC and can be considered as a “blue-carbon wealth contribution.” As the CSCC differs across the globe, the effect of country-specific inclusive wealth is also different. Additionally, as the CO2 uptake of coastal ecosystems varies globally, blue carbon wealth is redistributed between countries.

Australia’s coastal ecosystems save the rest of the world climate-related costs of around USD 23 billion a year

Based on estimates for blue-carbon sequestration and country-specific climate damages, we calculated the wealth contribution and redistribution arising from blue carbon. This reflects the fact that carbon sequestration in one country reduces climate damages in other countries, and vice versa. These estimates can then be summarized in a “net” position, which indicates whether a country provides—in net terms— blue-carbon wealth to other countries or whether it receives (in net terms)—blue-carbon wealth from others. For example, the coast of Australia—which contains around a quarter of the global salt marsh area, and 13 percent and 7 percent of global seagrass and mangroves areas, respectively—has the largest coastal blue-carbon sequestration potential (10.6 million metric tons of carbon per year). This equates to a wealth contribution of USD 25.0 bn—obtained by multiplying their carbon sequestration with the global estimate for the SCC.

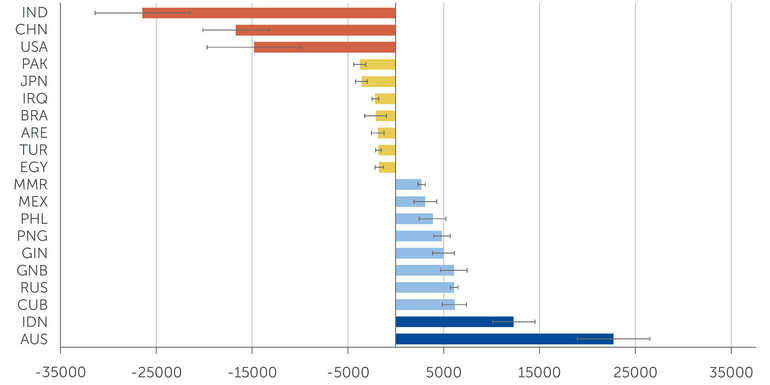

Chart: Positive and negative net wealth redistribution (in million USD)

However, Australia only sees a small portion of this benefit as the reduction of climate damages is global. Therefore, using Australia’s CSCC (USD 7.5 per metric ton of CO2 ), we estimate its domestic contribution to blue-carbon wealth from avoided climate damages at USD 0.291 bn per year. Consequently, the remaining benefits arising from blue-carbon sequestration in Australia take place abroad and amount to USD 24.7 bn per year—estimated by multiplying Australia’s blue-carbon sequestration by the sum of the CSCC of all other countries. At the same time, Australia also benefits from carbon sequestration in other countries, which we estimate at USD 1.9 bn per year. Clearly, the outbound contribution exceeds the inbound figure, such that Australia provides a net outbound contribution to blue-carbon wealth of USD 22.8 bn per year to the rest of the world.

Long coastlines are beneficial, but climate change costs also factor into net contribution

The results for Australia are driven by a relatively high level of coastal blue-carbon sequestration and a relatively low estimate for domestic marginal climate impacts. Accordingly, the three countries with the largest country-level social cost of carbon—the U.S., India, and China—are also the countries that benefit most from carbon sequestration taking place at home and abroad. The rest of the top 10 net recipient countries of blue-carbon wealth are shown by the red and orange bars in the chart below. The blue and green bars indicate the top 10 donor countries; after Australia come Indonesia, Cuba, and Russia.

Related publication

References:

Bertram, C., et al. (2021). The Blue Carbon Wealth of Nations. Nature Climate Change 11: 704–709.

Rickels, W., und M. Quaas (2021). Mapping ‘Blue-Carbon Wealth’ Around the World. Carbon Brief, 12. Juli.