News

Germany earns less on its foreign investments than other countries

In the research paper "Exportweltmeister: The Low Returns on Germany's Capital Exports" the authors Franziska Hünnekes and Christoph Trebesch (Kiel Institute) as well as Moritz Schularick (University of Bonn) calculated investment returns and value changes of German foreign investments across seven decades. They then compared this with the investment returns of 12 other industrialized countries and the returns on domestic investments.

Germany is the worst performer among the G7 countries. Investors from Germany receive particularly low returns on equity investments, which are 4 percentage points lower than those of other countries.

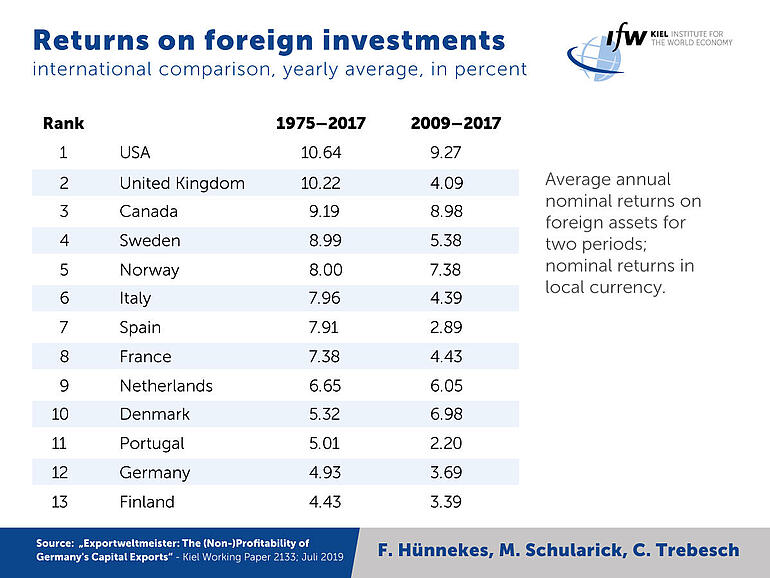

The following table shows a ranking of countries according to their average return on foreign investment, taking into account all countries for which sufficiently detailed data are available. From 1975 to 2017, Germany ranked 12th, with only Finland performing worse. The picture is similar if one looks at the years since the financial crisis (2009–2017) in which Germany ranks 10th. If inflation (real return) is also taken into account, German foreign investments only perform slightly better in 9th place.

Almost 300 billion euros of German capital are sent abroad every year (net outflows). In the last 10 years alone, Germany exported 2.7 trillion euros of capital, which corresponds to about 70 percent of the gross domestic product of 2017. German banks, companies, and private investors are the central players in this massive outflow of capital.

In the decade since the financial crisis of 2008 alone, Germany could have gained an additional 2 to 3 trillion euros of wealth if the returns on foreign assets had corresponded to those of Norway and Canada, respectively. This corresponds to 70 to 95 percent of the German gross domestic product of 2017 or, on a per capita basis, 37,500 or 28,000 euros of foregone gains for every German citizen (compared to the returns of Norway and Canada).

"Germany is the world's largest capital exporter but it achieves only very modest returns in international comparison. We urgently need to understand the reasons for this, because asset losses of this magnitude are a problem for an ageing economy like Germany’s," says Christoph Trebesch, one of the authors of the study and head of the Research Area "International Finance and Global Governance" at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

The results are consistent with earlier studies, among others by the Kiel Institute, which have compared German foreign investments with the financial investments of foreigners in Germany. According to these studies, capital outflows from Germany in the last 10 years have yielded higher returns than the capital inflows into Germany. Hence, German investments followed the returns. However, in international comparison, Germany’s return on foreign investments is at the lower end of the ranking.

A big part of the explanation for Germany’s low returns abroad are valuation losses. In most years since the 1970s, the value of the German investment portfolio has stagnated or declined, while the portfolios of other countries have tended to increase in value. Exchange rate effects cannot explain this result.

"The large stock of German foreign assets is often seen as beneficial—for example to protect against lower growth in Germany with its ageing society or against negative income shocks in Germany. But we can show with our calculations that both aims are hardly achieved with Germany’s current foreign asset portfolio," says Franziska Hünnekes, research assistant at the Kiel Institute and at LMU Munich and an author of the study.

An increasing problem is that investors from Germany are investing less and less in younger, dynamic economies in developing and emerging countries. The share fell from 25–30 percent in the 1980s to less than 10 percent in 2017. At the same time, the share of investments in ageing economies increased, especially in Europe. "In order to hedge against Germany's demographic risks, it is essential to reverse this trend towards the so-called "home bias", i.e. to invest more in developing and emerging countries again," says Trebesch.