Supply Bottlenecks

Rather than leading out of the crisis, the road led further into it

Spring 2021, a shipping accident in the Suez Canal that demonstrated the vulnerability of the globalized world and its dependence on a smooth exchange of goods. Hopes for a quick return to normality quickly evaporated. The Ever Given accident marked just the beginning of a chain of events that disrupted supply and demand across the world markets. The Kiel Institute analyzed delays in container shipping in real time and calculated the cost of the supply bottlenecks to industry and consumers.

At the beginning, sensationalism and fascination prevailed, with people amazed at how this huge ship blocked the entire Suez Canal, simply because of a very slight rotation, and how a dredger, which itself was pretty powerful, looked like a children’s toy at the ship’s bow. The pictures went viral around the world and caused general astonishment. It took only a short time, though, for the economic impact of the accident to come to the fore. One of the most important, perhaps the most important lifeline for the global movement of goods blocked? For how long? What are the consequences?

The Kiel Institute provided facts just over a day after the incident. Some 98 percent of all cargo ships traveling between EU and China pass through the Suez Canal. This means that around eight to nine percent of German imports and exports of goods were blocked. This mainly affected electronics, machinery (parts), and textiles.

Our rapid response and precise information was made possible by the evaluation of ship position data in real time, which trade researcher Vincent Stamer carries out with the Kiel Trade Indicator. He records docking and departing container ships at 500 ports worldwide. In addition, he analyzes ship movements in 100 maritime regions and measures the effective utilization of container ships on the basis of draft information.

Analysis of ship position data in real time

With the help of this big data analysis, Stamer estimates the expected imports and exports for 75 countries and regions, using country-port correlations even for countries without their own deep-sea port.

The Kiel Trade Indicator’s algorithm learns as the data become available (“machine learning”), so that forecast quality continually improves over time.

“With the Kiel Trade Indicator, the Kiel Institute provides an early economic indicator of unprecedented quality and quantity,” said the then President of the Kiel Institute Gabriel Felbermayr at the tool’s presentation. “High-frequency data offer us the exciting opportunity to read or forecast economic swings with a very small time lag. Benefits include the ability of business and policy makers to react much earlier to emerging upheavals and take countermeasures.”

In this specific case, the Federal Statistical Office did not publish Germany’s trade figures for April—which would have shown the possible consequences of the Ever Given disaster, which happened at the end of March—until the beginning of June. The Kiel Trade Indicator showed as early as April (and definitively at the beginning of May, i.e., more than a month before the official figures were published), that the recent upward trend in German trade had come to an end in April and that imports and exports were flatlining or declining slightly.

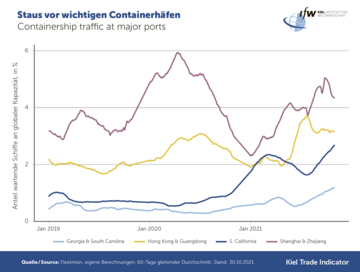

The following months brought little improvement—on the contrary. The Ever Given incident marked just the beginning of a chain of events that completely unbalanced supply and demand across the world markets. Second and third waves of COVID-19, the closure of production facilities, individual terminals, and even entire ports in China, and increased demand for everything that makes people comfortable in their own homes compounded the problems. As a result, the carefully choreographed network of container shipping became increasingly out of step.

Correlation between new orders and production reveals damage

Supply bottlenecks are also a major reason why the German economy’s catch-up process is being delayed time and again and inflation rates are soaring beyond all predictions. As early as the summer, Stefan Kooths, head of business cycle analysis and acting vice president of the Kiel Institute, summed up the situation as follows: “The German economic boiler is under steam. Demand, additionally fueled by pent-up purchasing power and government stimulus programs, is faced with the challenge of limited supply, in part due to supply bottlenecks. All in all, the signs are pointing to strong expansion. However, this is driving up prices in areas where production capacities are not yet able to keep pace with rising demand.”

The consequences of supply bottlenecks for German industry are immense. The pile of unfilled orders continues to grow and there is an increasingly urgent shortage of intermediate products. In a forecast published in June, economic researcher Klaus-Jürgen Gern concluded that a lack of supplies is likely to cost the German economy around EUR 25 bn over the course of the year. The calculation is based on data on the historical relationship between the level of incoming orders and production in industry in Germany since reunification. The estimation methodology was presented in the summer forecast of the Kiel Institute.

“In April, industrial production was already almost 11 percent below the level that incoming orders would actually have led us to expect. At present, it could be at least five percent higher if sufficient production materials and intermediate products were available,” said Klaus-Jürgen Gern.

The tentative signs of recovery seen in the summer proved misleading. In August, the Kiel Trade Indicator showed that there were 20 percent fewer goods on the Red Sea, the most important trade route between Asia and Europe, than would be expected under normal circumstances. Meanwhile, nearly 14 percent of all goods shipped worldwide were stuck in congestion, nearly one in seven products. In October, around 10 percent of global freight capacity was tied up in congestion and could not be loaded or unloaded.

In late summer, Vincent Stamer warned: “Maritime trade remains disrupted, the terminal closure at Ningbo is exacerbating the bottlenecks in container traffic. If goods trade with China does not quickly return to normal, the crisis also threatens to make itself noticeable in Christmas commerce with missing products and higher prices.” In fact, some wishes for Santa Claus, such as for a game console, remained unfulfilled or could only be realized at a significant price premium. (see Kiel Trade Indicator Update 09/2021)

Germany more affected by supply bottlenecks than other countries

German industry operated at half speed throughout 2021 because it lacked upstream products from the Asia-Pacific region. “The supply bottlenecks are estimated to cost the industry EUR 40 bn in value added this year,” said economic researcher Nils Jannsenat the presentation of the fall forecast in October. The calculation still stands today, and looking back he states: “The supply problem is a major reason why economic output in Germany has recently lagged behind its pre-crisis level, while in many other countries it has already exceeded its pre-crisis performance. The overall economic impact of the supply bottlenecks is particularly serious in Germany, partly because the manufacturing sector accounts for around 20 percent of total value added, which is significantly higher than in many other countries. By comparison, the share in France is around 10 percent.”

The global economy has never previously experienced supply disruptions like those in 2021. A lack of comparable data and empirical benchmarks made it immensely difficult to assess the situation and ask what the consequences would be. With the Kiel Trade Indicator and its profound methodological estimation procedures, the Kiel Institute provided valuable forecasts at an early stage, making it possible to assess the situation correctly.