News

War experiences leave deep traces in employment biographies

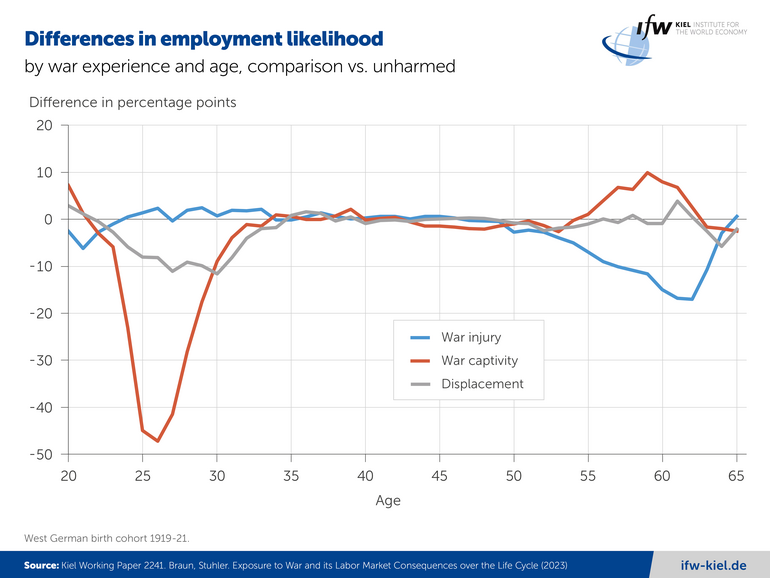

The authors examine the consequences of war for employment biographies in West Germany for the cohort born between 1919 and 1921 (Braun, Stuhler: Exposure to War and Its Labor Market Consequences over the Life Cycle ). Ninety-five percent of the men in this cohort fought in the war. In addition, the study looks at displaced persons who were between two and 60 years old at the end of the war.

"Our results show that war injuries reduce employment only in old age, presumably because that's when health problems become severe. On the other hand, former POWs postpone retirement to compensate for lost working time and income," labour economist and Kiel Institute Fellow Sebastian Braun says.

"The consequences of displacement are complex and depend heavily on the particular stage in the life cycle. Young people who are in the process of looking for an apprenticeship and older people at the end of their working lives tend to suffer the most. Historically, displaced women in particular often failed to re-enter employment."

According to the study, war injuries, such as gunshot wounds or amputations, led to retirement nearly a year earlier. In addition, injuries reduced monthly pension benefits by almost 10% compared to a person who retired without a war injury. However, additional pensions for war victims in Germany nearly offset this loss. In contrast, war injuries did not affect occupational success.

"Looking at the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, we expect that Russian and Ukrainian wounded will not necessarily be missing from the labor market in the immediate postwar period, but only when these veterans approach retirement age," Braun says.

Prisoners of war significantly less successful professionally

Almost two out of three men born between 1919 and 1921 were prisoners of war for at least six months. Many did not return to Germany until after the end of the war, typically at an age when they would have completed their education in peacetime and been active in the labor market. War captivity shortened the working lives between ages 20 and 55 by an average of more than two years. Former prisoners of war were also significantly less successful professionally than former soldiers who escaped captivity.

Former POWs tried to compensate for the loss of working time and income in their younger years by working more in old age. On average, they retired almost half a year later in comparison.

Displaced persons from the 1919 to 1921 cohort suffered severe losses in their working lives and careers. In the years after the end of the war, the employment probability of displaced persons was about ten percentage points lower than that of non-displaced persons. At retirement age, their wealth income was almost two-thirds lower.

Consequences of displacement for two- to 60-year-olds: Great variation by age and gender

An extension of the study also shows the effects of displacement on the employment biographies of other cohorts and civilians. The central finding here is that the consequences vary greatly depending on the age and gender of those affected. The impact on education was worst for individuals transitioning from school to vocational training. Here, men lost an average of 0.7 years of education due to displacement, and women 0.4 years – with corresponding adverse effects on their careers.

The employment loss was particularly severe for older people, especially women. Women who were 40 to 50 years old at the time of displacement lost, on average, more than two years of employment, and 50 to 55-year-old men 1.5 years. Many older displaced persons, again especially women, often never regained a foothold in the labor market and never found a job again after the expulsion.

"Our findings show that policymakers should support war veterans specifically at the end of their working lives, even if they managed to re-enter the labor market in the postwar period," says Braun. "Additionally, quickly integrating displaced persons into the labor market and education system is crucial. Special attention should be paid to young adults transitioning from school to vocational training and to groups disadvantaged in the labor market."