News

Cereal exports: Ukraine default hits African countries hard

”Due to the war, Ukraine is likely to be initially cut off from the global economy—trade routes have been cut, infrastructure destroyed, and all remaining production factors are likely to be directed towards a war economy. As the country is one of the most important grain exporters in the world, and especially relevant for Africa. Losing Ukraine as a supplier will noticeably worsen the supply situation across the continent,” says Hendrik Mahlkow, trade researcher at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

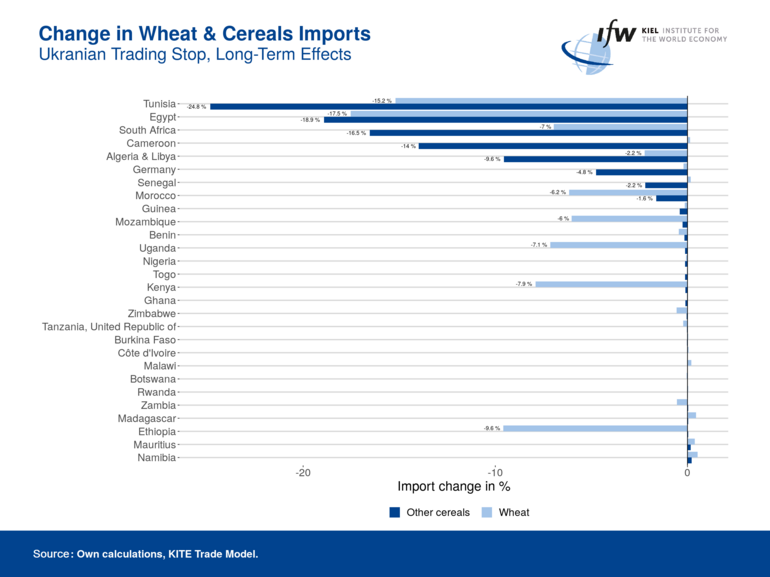

Jointly with Tobias Heidland, Research Director for International Development and member of the Africa Research Cluster, he used the KITE (Kiel Institute Trade Policy Evaluation) trade model to simulate the long-term consequences for Africa of an end of exports of Ukrainian wheat and other cereals for food production, such as corn or sorghum. The model calculations did not include cereals used as animal feed, such as corn. Accordingly, Tunisia and Egypt, in particular, would be negatively affected.

In Tunisia, the country's total wheat imports would permanently decrease by over 15 percent, and imports of other cereals would decrease by almost 25 percent. Egypt would import over 17 percent less wheat and almost 19 percent less other cereals, while South Africa would import 7 percent less wheat and over 16 percent less other cereals.

Imports of other cereals would also be noticeably lower in Cameroon (-14 %) and Algeria and Libya (-9.6 %, aggregated in the trade model). Wheat imports would drop significantly in Ethiopia (-9.6 %), Kenya (-7.9 %), Uganda (-7.1 %), Morocco (-6.2 %), and Mozambique (-6 %).

”Ukraine's central importance to Africa's food supply is evident from our estimates, especially in countries that consume grains they buy on the world market. Ukraine is irreplaceable as a grain supplier, even in the long term. Its failure worsens Africa's supply and also drives up prices,” Mahlkow said.

”One way of increasing the world market supply of cereals quickly would be to reduce growing biofuel and to use the land for cereal grains. In Germany alone, this would affect three percent of all cropland. However, such a decision must be made fast, as sowing begins in the coming weeks."

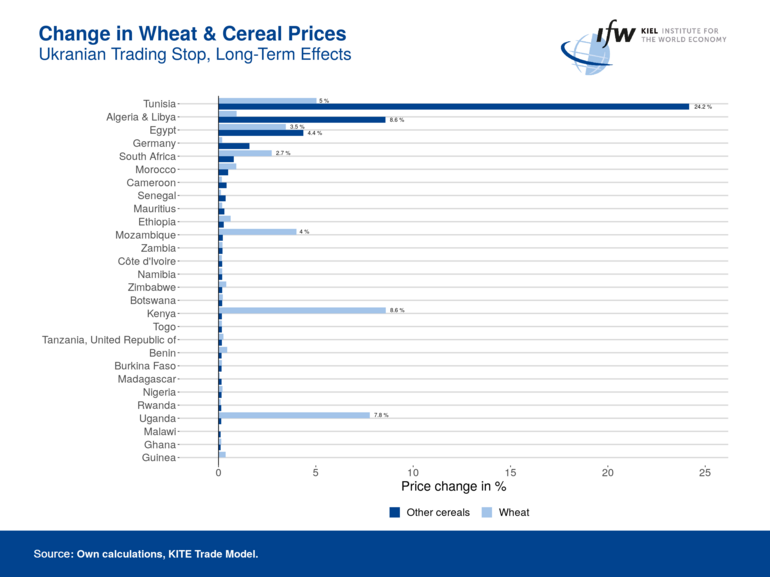

Prices rise dramatically in some cases

If less grain is available, prices will rise as a result, in some cases dramatically. According to the simulation, other cereals would become more than 24 percent more expensive in the long term in Tunisia, almost 9 percent in Algeria and Libya, and more than 4 percent in Egypt. The permanent increase in the price of wheat would be nearly 9 percent in Kenya, almost 8 percent in Uganda, 5 percent in Tunisia, 4 percent in Mozambique, and over 3 percent in Egypt.

Western countries would be far less affected than the African continent by the loss of Ukraine as a grain supplier. Western countries are not as dependent on imports and can better compensate for the shortfall. Germany, for example, would import 4.8 percent less other cereals in the long term, which would result in a moderate price increase of around 2 percent.

”This raises memories of the Arab Spring when sharply rising food prices drove people into the streets and sparked protests. The international community should now step up its efforts to help African countries improve their food production. This will make them more resilient to supply shocks in the long term and is also a smart strategy in light of the worsening climate change,” says Tobias Heidland of the Kiel Institute's Africa Cluster.

”In global crises, the rich countries of the West have a special responsibility that they should be aware of when deciding on their policy reactions because the consequences of global supply crises affect people with low purchasing power particularly negatively. In the case of globally traded goods, price shocks hit people in poorer countries hardest and, in the case of food price shocks affect especially those in cities.”

The trade model KITE (Kiel Institute Trade Policy Evaluation) simulates the long-term and permanent changes in trade flows when conditions change. That can happen, for example, through the emergence of trade barriers, the loss of an entire country as a trading partner, or through trade facilitation, such as new free trade agreements.

The short-term consequences and adjustment processes are not reflected in the model. In many cases, they are likely to cause even greater distortions than in the long term, as adjustments in production and consumption patterns take time.