Kiel Institute Highlights

Norway - the future European Hub for CO2 Storage?

It is an uncomfortable truth that politicians, and also many climate activists, are reluctant to face: without negative emissions, it will be impossible to achieve the 1.5°C target. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is an indispensable technology in this regard. In Germany, however, underground storage is prohibited, not least due to pressure from the public, which is skeptical of CCS. Norway is much further ahead in this regard. The technology is accepted as part of the climate solution and politicians are flirting with new business models. However, the population does not want to go that far, as our empirical study shows. Norway is not set to become Europe’s CO2 dumping ground.

for filtering CO2 from the air has been located in

Hinwil, not far from Zurich. Climeworks opened the

world’s largest direct air capture (DAC) plant in Iceland

in September 2021.

On the way to CO2 neutrality and thus to the 1.5°C target, CCS, i.e., capturing and storing CO2, is an indispensable technology (IPCC, 2018). It could in particular help to avoid CO2 emissions from cement factories, in the chemical industry, and from waste incineration plants by capturing the released CO2 and storing it underground, e.g., in empty oil or gas fields.

Too many associate this kind of storage with nuclear waste disposal.

It could also be used to remove already emitted CO2 from the atmosphere and render it harmless. Legally, however, underground CO2 storage is largely prohibited in German states with geologically suitable conditions, such as Schleswig-Holstein. This ban was enforced primarily as a result of public pressure. Too many associate this kind of storage with nuclear waste disposal. A key difference here is that a leak from a geological carbon storage facility would primarily harm the climate; the negative impact on the immediate environment would be minor.

Norway has plenty of capacity for storing CO2 – also from abroad

Therefore, there are currently no plans to store CO2 on German territory, neither under the seabed nor under the mainland. Nevertheless, Germany would also like to use this technology in the future and at least capture CO2 from domestic installations. According to the Industrial Strategy 2030 set out by the Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (BMWI, 2019), it is to be stored under the North Sea off the coast of Norway or Scotland. Starting in 2025, for example, there are plans to store 1.5 MtCO2 annually in Norway as part of the Northern Lights pilot project. Total storage potential is many times higher, at 56,000 MtCO2. Since it is not worthwhile building the infrastructure for use by Norway alone, the intention is to import CO2 that is captured in Germany and Sweden as well. In the medium term, there are plans to set up a transport and storage infrastructure between the countries bordering the North Sea (Northern Lights PCI, 2020).

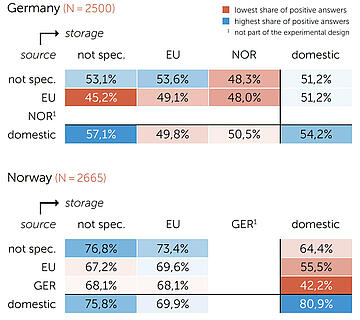

One advantage for Germany would be that for the time being nothing would have to be changed around the legal status of CO2 storage, which is unpopular with the public. However, in a survey conducted by the Kiel Institute together with Norwegian project partners at the Norwegian Research Center (NORCE), storing CO2 captured in Germany abroad does not change the public’s perception of the technology. About half of the respondents in Germany viewed a presented CCS project positively and it made no difference whether the storage was to take place in Germany, Norway, or another European country (see table). In the Norwegian Research Council-funded project, titled PerCCSeptions, 2,500 German and 2,665 Norwegian participants were asked about their assessment of one carbon import-export dyad. The survey took place in late 2019 and the participants are representative of the 18–65 age group with access to the Internet.

Positive attitude to CCS in Norway, but no interest in being “Europe’s carbon dumping ground”

Norwegian respondents were much more positive on average about the CCS project presented. Despite the general openness toward CCS, however, respondents reacted very critically when it came to importing CO2 from Germany or other European countries to store it domestically under the North Sea. Norwegians do not seem to be entirely comfortable with importing other people’s “garbage,” whereas 81 percent support the storage of domestic CO2 in Norway. The fundamentally different perceptions of CCS in Germany and Norway can be easily explained. In Germany, few people have even heard of it and politicians hardly ever talk about it. The situation is quite different in Norway. There, most people know what CCS is and, due to the important role of the oil and gas industry, the government and the population regard CCS as an opportunity to use the now empty oil and gas fields as CO2 storage sites in the future and to create a new industry.

Toward a win-win situation: CCS image campaign in both countries

So political persuasion is still needed in both countries. In Germany, it would be important to talk publicly about CCS in the fi rst place and to stress that it is not about retaining coal-fired power plants but about being able to continue producing cement or operating waste incineration plants. After all, these are emissions that cannot be completely reduced to zero by technical innovation or substitution. But with CCS, it would be possible to capture the CO2 before it causes damage in the atmosphere. Initial studies show that acceptance increases when it becomes clear that it is about mitigating process emissions that are difficult or impossible to eliminate and not about prolonging the use of coal-fired power plants (Dütschke et al., 2016). In Norway, the message should be that the associated research and development investment, which is to a large extent state-funded, is only worthwhile if CO2 is imported from other countries as well in the future.

Related publication

References:

BMWI – Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz (2019). Industriestrategie 2030: Leitlinien für eine deutsche und europäische Industriepolitik Berlin.

Dütschke, E., et al. (2016). Differences in the Public Perception of CCS in Germany Depending on CO2 Source, Transport Option and Storage Location. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 53: 149–159.

IPCC – Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2018). Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfi eld (eds.). In Press.

Merk, C., et al. (2022). Don‘t Send Us Your Waste Gases: Public Attitudes Toward International Carbon Dioxide Transportation and Storage in Europe. Energy Research & Social Science 87: Article 102450.

Northern Lights PCI (2020). CCS and the EU COVID-19 Recovery Plan. The Positive Economic Impact of a European CCS Ecosystem. Retrieved from northernlightsccs.com