News

Kiel Institute summer forecast: High prices and supply bottlenecks put the brakes on recovery

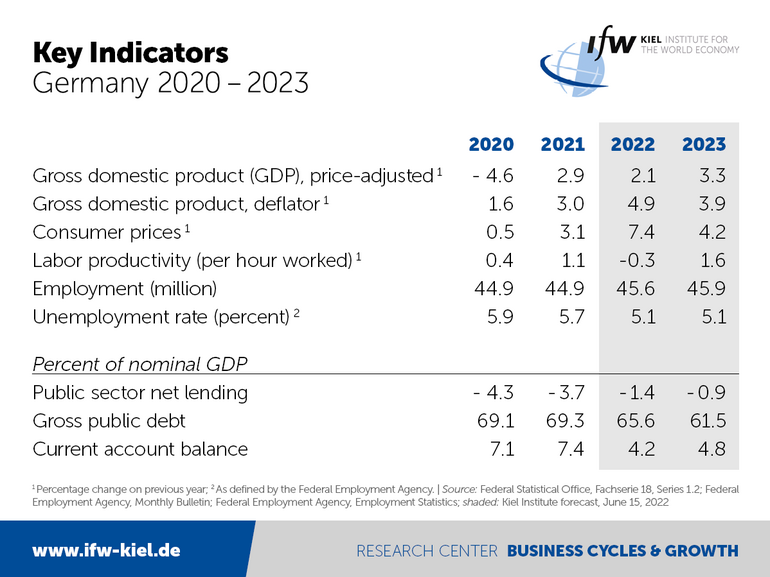

"Although the buoyant forces of the German economy are intact, they are now acting with significantly reduced strength," comments Stefan Kooths, Vice President and Head of Forecasting at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, on the summer forecasts for Germany ("Slowly progressing recovery") and the world ("Inflation is curbing global growth") published today. According to these forecasts, German GDP is likely to return to its pre-crisis level in the third quarter and then grow again at rates of around 1 percent, noticeably stronger than in the previous three quarters.

The upswing is being supported firstly by private households, which are still sitting on very high savings of around 200 billion euros as a result of the pandemic now strengthening their purchasing power. Secondly, manufacturers face record high order backlogs. Since the start of the pandemic, the overall order backlog has increased by 30 percent. This corresponds to more than 15 percent of annual production or value added of around 100 billion euros.

At the same time, both sectors have been negatively affected by recent economic upheavals. Due to supply bottlenecks, industrial production was recently 10 percent lower than would have been possible in view of incoming orders. The bottlenecks are likely to continue well into 2023.

Increasing risk of inflation becoming entrenched

Private households are suffering from the sharp rise in consumer prices, which is even stronger than previously expected. In 2022, the inflation rate is expected to reach a near-record 7.4 percent, significantly higher than the price increases during the oil crisis of the 1970s. In 2023, when supply bottlenecks ease and crude oil prices cease to have any further impact on the inflation rate, the rate will probably fall to 4.2 percent.

"The current inflationary pressure is primarily a consequence of the massive worldwide fiscal programs during the pandemic, which in turn were largely financed by central banks, including the European Central Bank (ECB). Its initial signals to normalize monetary policy came far too late and have so far been too timid in view of the substantial miss of targets," Kooths said.

"This increases the risk of strong devaluation of money becoming entrenched via higher inflation expectations. What then looks like a wage-price spiral is in fact the result of lost confidence in price stability. Germany is heading for low-growth years anyway— whether this turns into stagflation is in the hands of monetary policy."

The recovery in employment from the Covid-19 crisis is continuing, notwithstanding the war in Ukraine. After 5.7 percent last year, the unemployment rate is expected to fall to 5.1 percent in both forecast years.

Current account surplus declines significantly

Public budgets are benefiting from a sharp rise in tax revenues in the area of sales and profit taxes and from an end to the Corona aid packages. The fiscal situation is therefore significantly better than expected in 2021. The budget deficit will fall to EUR 54 billion (1.4 percent of GDP) in 2022 and to EUR 37 billion (0.9 percent) in 2023. Gross public debt is then expected to be close to the 60 percent mark again.

German exporters are also sitting on high order backlogs, which they can work off as soon as the supply bottlenecks ease. Exports are expected to increase by 3.4 percent in 2022 and then by 6.5 percent in 2023. Imports are expected to increase by 6.6 percent (2022) and 5.6 percent (2023) due to high demand for capital goods and foreign travel. In particular due to high prices for imported goods— - mainly because of increased raw material costs and the weak euro— - Germany's much-criticized current account surplus will fall significantly from over 7 percent to 4.2 percent (2022) and 4.8 percent (2023).

Global economy: outlook noticeably gloomier

Global production is also being impacted by strong inflation and supply bottlenecks. In addition, China's strict no-Covid policy is cutting growth this year by around 0.2 percentage points. The global economy is now expected to grow by only 3.0 percent this year and by 3.2 percent next year, representing a downward revision from the Kiel Institute spring forecast by 0.5 and 0.4 percentage points.

"It would be problematic if inflation proved to be more persistent than central banks expect," Kooths said. "Then monetary policy would have to step on the brakes more than assumed, with the risk of a recession in advanced economies and a pronounced deterioration in financial conditions in emerging markets."